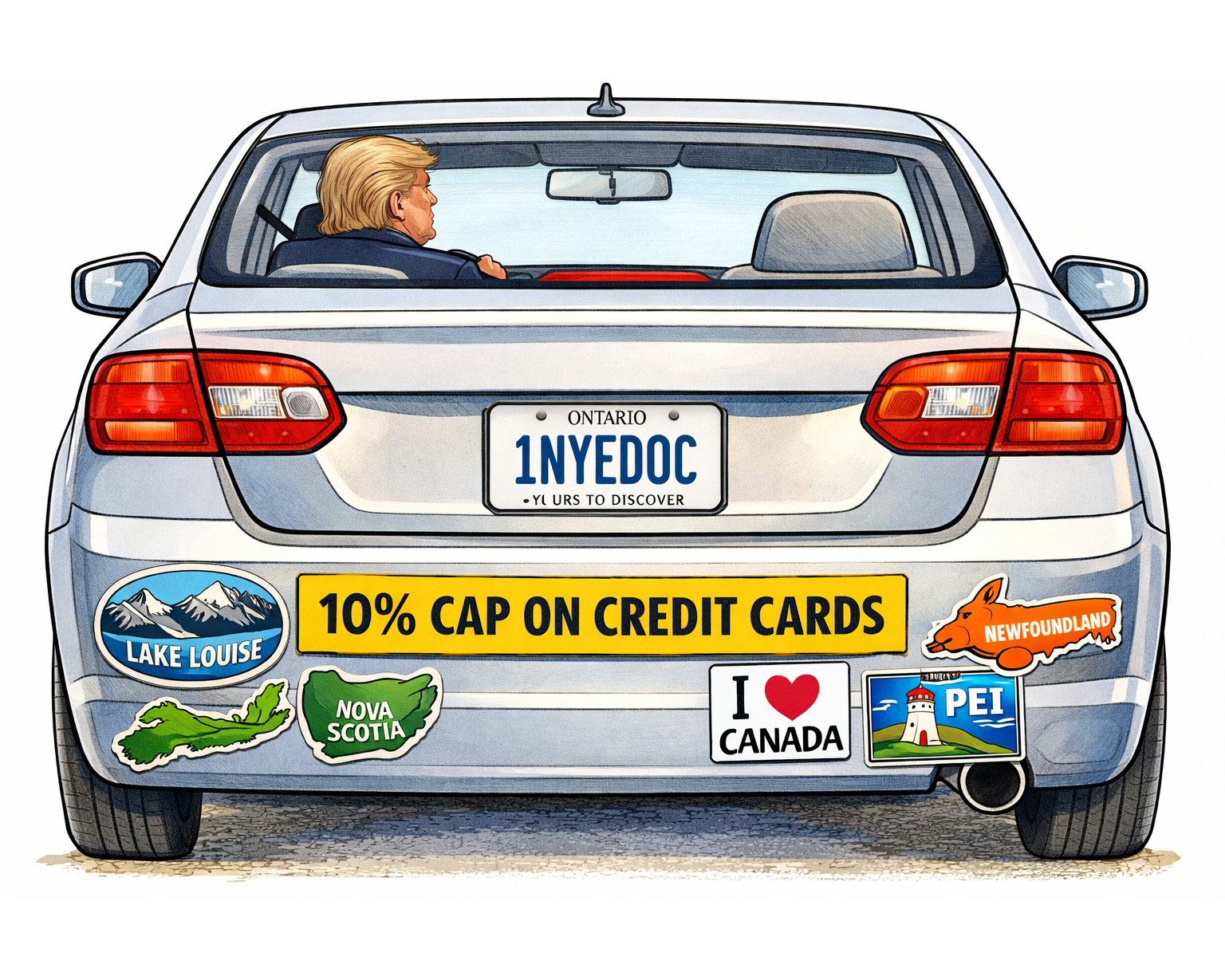

What Trump Gets Wrong About Credit Cards

Why a 10 percent rate cap would do borrowers more harm than good

What the CLA has explained

Over the past several years the Canadian Lenders Association has spent much of its time explaining a deceptively simple point to policymakers: APRs are not arbitrary. They are built from hard arithmetic. The rate on a credit card, loan or BNPL product is the sum of five things: the cost of capital, expected credit losses, fraud, compliance and servicing, and the uncertainty of human behaviour over time.

Cap the rate and none of those costs disappear. They merely migrate. Lenders will recover them through fees, higher minimum payments, shorter grace periods, fewer rewards, or by refusing to lend at all.

Price controls do not eliminate costs. They just make them harder to see.

Risk-based pricing is not a gift to banks. It is what allows credit to exist on a continuum rather than as a yes-or-no gate. In Canada it is what permits newcomers, young borrowers, gig workers and those rebuilding credit to be served inside the regulated system instead of pushed to its fringes.

Remove the ability to price risk and the continuum collapses. The safest borrowers are still approved. Everyone else is politely declined.

That is why blunt caps rarely benefit the people politicians claim to be protecting. High-income revolvers with pristine credit still get cards. Marginal borrowers lose them.

Canada has already tested this theory. In repeated debates over statutory interest-rate ceilings, the CLA has warned that lowering maximum allowable APRs would not reduce the cost of credit so much as change its shape. Higher-risk consumers would be displaced into instalment products, fee-heavy structures, or unregulated channels where protections are weaker and transparency thinner.

Those warnings were not ideological. They came from portfolio data, fraud statistics and borrower-migration patterns that lenders see long before they appear in official reports.

When regulated credit becomes too constrained, credit does not vanish. It goes underground.

America is about to relearn the lesson

A 10 percent cap on U.S. credit cards would follow the same script: Lenders would tighten underwriting. Fees would rise. Rewards and grace periods would shrink. Borrowers who cannot be priced for risk would be priced out entirely.

The irony is that the system would become less consumer-friendly, not more. The headline rate would look better. The real cost of credit would become more opaque.

The debate over rate caps is often framed as one between compassion and greed. In reality it is a choice between precision and blunt force.

Precision means better data, stronger underwriting, fraud controls and targeted consumer protections. Blunt force means a number picked for political convenience, imposed on a system that does not run on slogans.

Credit markets, like all markets, work best when prices are allowed to convey information. Muffle the signal and misallocation follows.

The Canadian Lenders Association sees Mr Trump’s proposal not as a template but as a cautionary tale. Credit systems fail not when prices are visible, but when risk is mispriced, costs are hidden and access collapses for those without alternatives.

Affordable credit is best achieved through careful system design, not headline-friendly mandates.

Five key points

- APRs reflect real economic risk: The CLA has consistently shown that APRs incorporate cost of capital, expected losses, fraud, compliance, and servicing, not discretionary pricing.

- Rate caps do not remove cost, they hide it: When rates are capped, lenders recover costs through fees, higher minimum payments, reduced grace periods, and the removal of consumer benefits.

- Risk-based pricing is what preserves inclusion: Without the ability to price for risk, newcomers, younger borrowers, gig workers, and those rebuilding credit are pushed out of the regulated system.

- Canada has already seen the displacement effect: Lower statutory rate ceilings have led to borrower migration into less transparent, higher-cost, or unregulated alternatives rather than lower overall costs.

- The U.S. proposal risks repeating a known failure: A 10 percent cap would likely shrink access, increase hidden costs, and weaken consumer protection, even if the headline rate appears more attractive.

Sign up for the CLA Finance Summit Series